Biography

Stefan Brecht was born in 1924 in Berlin, son of Bertolt Brecht and Helene Weigel. When he was 9 his parents fled Germany, taking him and his sister Barbara with them to live in Denmark, then Sweden and then Finland, arriving in Santa Monica, California in 1941. He finished high school there and went to UCLA, but before receiving a B.S. in chemistry – his father’s suggestion – he was drafted. It was 1945, near the end of WWII; the Army sent him to U. Chicago to add Japanese to the list of languages he’d learned under duress. After a quick (though honorable) discharge for migraine headaches, he completed his BS at UCLA and used the GI bill to go to Harvard. Although his family left the US immediately after the House Unamerican Activities Committee investigation of his father in 1947, Stefan Brecht chose to stay. His study of Hegel earned him a Masters in 1948; his doctoral dissertation, The Place of Natural Science in Hegel’s Philosophy, was accepted by Robert Paul Ziff, Henry Aiken and John D. Wild in 1959.

While writing his thesis, he often visited his family, by then in East Germany, where his first son was born, though he did not marry. He travelled in Europe, spending time in Spain and France, and hitch-hiked through the US from Hoboken to San Francisco. He taught philosophy, briefly, at the University of Miami in 1957, and there wrote what was perhaps his first finished piece in English (his master’s thesis was in German), “Why Miami?”. It’s probably at this time that his abiding interest in Haiti began.

He pursued postdoctoral studies in Hegel and Marx at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, in the company of Mary McDonough, whom he had met in Boston. Two children were born, and Stefan, now married, moved with his young family to New York in the mid 60s.

Also new in New York in those years were race riots, psychedelics, and the anti-war rallies and marches in which the Living Theatre, the Open Theatre and Bread and Puppet Theatre’s street and park shows were prominent. Downtown, near where Brecht lived, the Ridiculous Theater, Jack Smith, Robert Wilson, Merce Cunningham, Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor did shows in loft spaces, bars and small theaters.

Excited by what he saw as a unique moment and a revolutionary theatre, Brecht quickly became involved. He joined Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company and, knowing that this time could not last, wrote up notes on what he was seeing everywhere, to preserve immediate detail. Never intentionally abandoning his work on Hegel and Marx, he now immersed himself in the dialectics of the world around him and recorded an analytical/poetic approach to the experience of observing what was revolutionary in theatre, music, dance and in the streets.

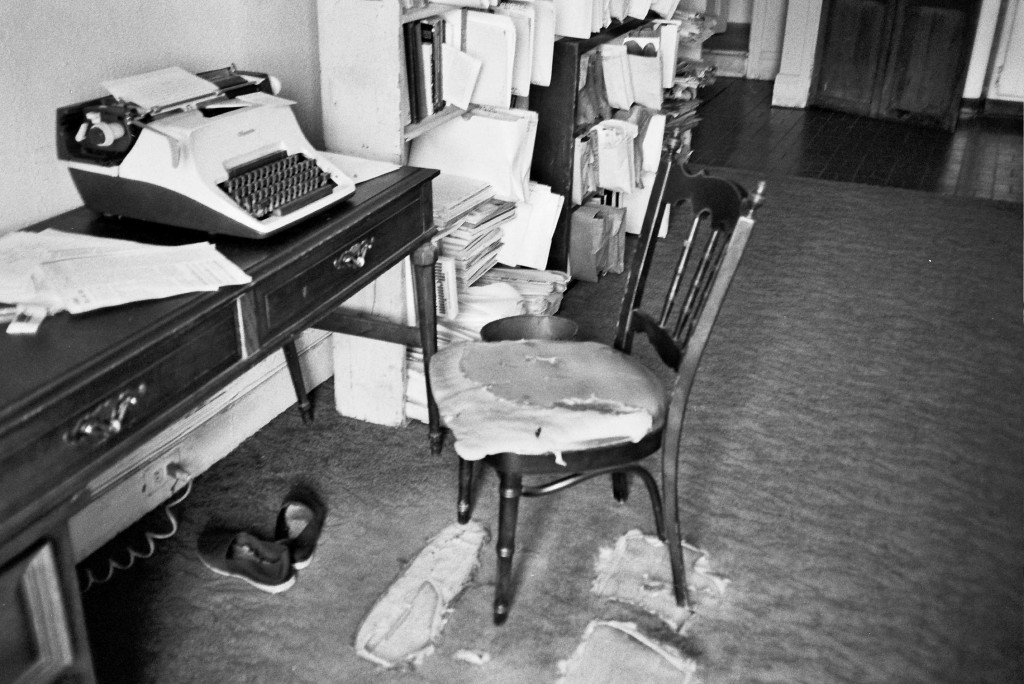

He developed his notes through interviews with directors and performers , many of whom he knew well, and through research, amassing files of clippings, scripts, programs, and interview transcripts and tapes (now, along with Brecht’s descriptions of many performances, archived in NYU’s Fales Library). Richard Schechner, who directed the Performance Group and edited TDR (The Drama Review), was the first to publish his writing on theatre: “The Conquest of the Universe” (title of a Ridiculous Theatre show) appeared in TDR in 1968; this was Stefan Brecht’s first published writing, apart from one poem published in a South Carolina newspaper and a piece on Sun Ra in Evergreen, 1968. Articles on Grotowski, LeRoi Jones, the Living Theatre, the Performance Group and the Bread and Puppet appeared in TDR through 1972. These, along with further writings on the same groups plus the Open Theater, Melvin van Peebles and Warhol, were collected into a book, New American Theater 1968 – 1973, published in translation (though never in English) by Mario Prosperi in Italy through Bulzoni Editori, 1974.

At some point, probably about the time the article-length pieces stopped appearing, he projected a series of nine books. The Original theatre of the City of New York, From the mid-60s to the mid-70s was to include:

- Book 1: The Theatre of Visions: Robert Wilson

- Book 2: Queer Theatre

- Book 3: Richard Foreman’s Diary Theatre: Theatre as Personal Phenomenology of the Mind

- Book 4: Morality Plays: Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre

- Book 5: Theatre as Psychotherapy for Performers

- Book 6: The 1970s Hermetic Theatre of the Performing Director

- Book 7: Theatre as a Collective Improvisation: The Mabou Mines

- Book 8: Black Theatre and Music

- Book 9: Dance

The first to appear, Queer Theatre (Methuen, 1978), was brief at 177 pages, comprised of descriptions of performances by Jack Smith, the Ridiculous Theater, and Larry Ree, among others, and Brecht’s experiences in and with them. Poems and bits of memory, along with history and a philosophical sortie, form often impressionistic collage.

He’d been seeing Robert Wilson’s shows since 1969. Brecht’s detailed description and analysis of the major 1971 production, Deafman Glance, was from an audience perspective, but his writing about Overture (1972) and A Letter for Queen Victoria (1974) came from close work over several years with the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, a group that coalesced around Wilson to develop those pieces, in which Stefan performed. In the long quotes and footnotes that characterize this series, The Theatre of Visions: Robert Wilson (Methuen, 1978) provides an account of Wilson’s early 60s years, when he moved from painting to therapeutic theatre work with children into dance and performance; it continues through 1977.

Brecht went on to complete his book on the Bread and Puppet Theater. Since street protests were so much a part of Peter Schumann’s presence in the city in 60s, Stefan took this book as a chance to give details of what New York, particularly the Lower East Side, was like in those days, and how it was that Schumann began his still un-funded (by NEA etc.) work, at such places as Judson Church, the Astor Library (later the Public Theater), and the former Jefferson Courthouse (now Film Anthology’s site). He portrayed, too, the development of Schumann’s artistry in the making of the sculptural masks. With an account of Schumann’s early years in Germany and arrival in New York, and descriptions of performances beginning in 1962 in New York and continuing through 1983 in Vermont, Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre (Methuen, 1988) appeared in two volumes of some 800 pages each.

For the book on Richard Foreman’s Ontological Hysteric Theater, he drew from Foreman’s high school records, interviews with Foreman, Kate Manheim and others, and from Foreman’s Manifestos and other theoretical writings, as well as from his own writings about shows from the 1968 Angelface through The Cure in 1986. For this book, since the art milieu, including the underground cinema of the 70s, was a strong force in Foreman’s work, Brecht gave an account of that, as well as sometimes detailed explorations of contemporary intellectual currents and the writings Foreman often cited as important to him. The manuscript seemed to expand toward infinitude as Brecht explored the writing style of Gertrude Stein (one of the writers cited by Foreman). With ill health approaching, Brecht was forced to abandon his writing, leaving two manuscripts – one on Foreman, and one on Stein, unfinished.

Writing poems was a lifelong habit; two books, Stefan Brecht: Poems, and 8th Avenue Poems, were published as was a book of his photographs, 8th Avenue.

He read deeply in science, literature, and history, and kept up a study of ancient American civilizations. He admired Bosch, Hokusai, Durer and especially Goya, about whose series of engravings, “Disparates”, he completed a book-length manuscript.

His marriage with Mary McDonough having broken up in the early 1980’s, he lived with and married Rena Gill, whom he’d met while writing about Ridiculous Theatre. The disease that interrupted his writing in 2001 was a form of Parkinson’s which gradually eroded his ability even to speak. He died at home, from a heart attack, in April, 2009.